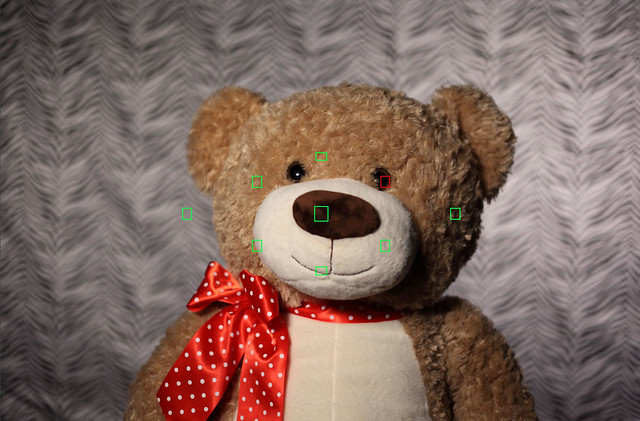

I want to talk specifically about autofocus when shooting portraits. To start off, let’s go back to the teddy bear portrait studio that I set up recently and look at a couple of example shots.

If you’re like most people, you’ll perceive the second image as being better than the first… the first one will probably seem like it’s not quite right, even if you can’t put your finger on why. Since this is an essay about focus, though, you probably spotted the difference pretty quickly– in the first image, the bear’s eyes are slightly out of focus, while in the second one they’re sharp.

As I mentioned earlier, shooting portraits can be tricky when you’re using your camera’s autofocus. Portraits are often shot with a fairly shallow depth of field, since you want your viewer’s attention to be on your subject and not on the godawful tiger-striped background that you’ve posed them against. (Again, don’t do that.) It’s extremely important that the subject’s eyes be in focus for portraits, because… well, because I said so and because every other photographer does too.

Here are a couple of closeups that illustrate the difference in my bear images.

In the image on the left, the nose is in clear focus, but the eye is blurry. On the right, the eye is in sharp focus but the nose is a little bit soft. Why the difference?

In the first image, I just let the camera pick its own focus point. It naturally gravitated toward the center of the image, found a nose that it could grab onto, and used that as the focus point. That’s great if you happen to have a weird fetish for noses, but it’s not great for portraits. In the second image, I told the camera that I wanted to use a specific autofocus point only, and then plunked that focus point right on the bear’s eye. Voila! I got exactly the shot I wanted.

If you can put a focus point right on one of your subject’s eyes, then do that. Some cameras have only one or a few autofocus points. Others, mostly high-end cameras, have eleventy billion of them scattered across the image. (IF you want to see this carried to an extreme, check out the 61 autofocus points on the Canon 5D Mark III. Also, if you’d like to give me one I will be happy to put each and every one of those autofocus points to good use.) As always, check your camera’s manual to figure out how to choose individual focus points, as the controls can vary quite a bit between manufacturers and even between different cameras from the same manufacturer.

If you can’t find an autofocus point that works, then you’ll just have to resort to manual focus. By now you probably know that it’s not so scary. Just flip the camera into manual focus mode, then turn the dial until you get what you want.

Thus endeth my wisdom about focusing for shooting portraits. I have one other topic to cover before I put autofocus to bed, but I’ll save that for another day.